Before James Hoffmann was the undisputed King of All Coffee Media, he was the musician King Seven, recording and performing music variously described as experimental, electronica, downtempo, and trip-hop, among other things. I’m not sure about those labels. I would say instead that his music strikes me as wholly Hoffmannesque: innovative and surprising while at the same time remaining oddly reliable and even comforting. As he worked on his first album, “Hidden EP,” in 2002, he likely didn’t know that some people (okay … maybe just me) were marking that year as the 80th anniversary of the first book published by the original King of All Coffee Media, William Harrison Ukers.

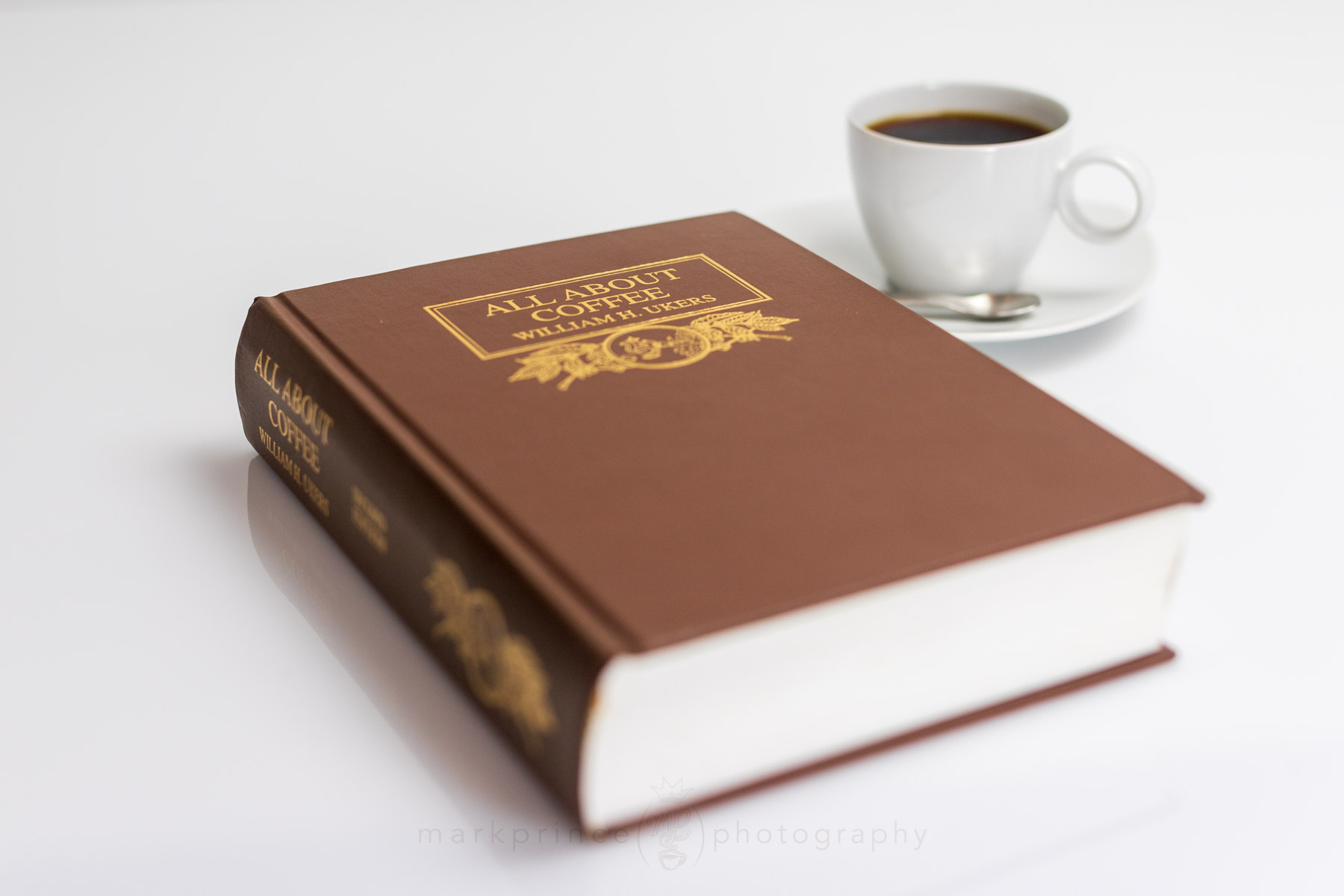

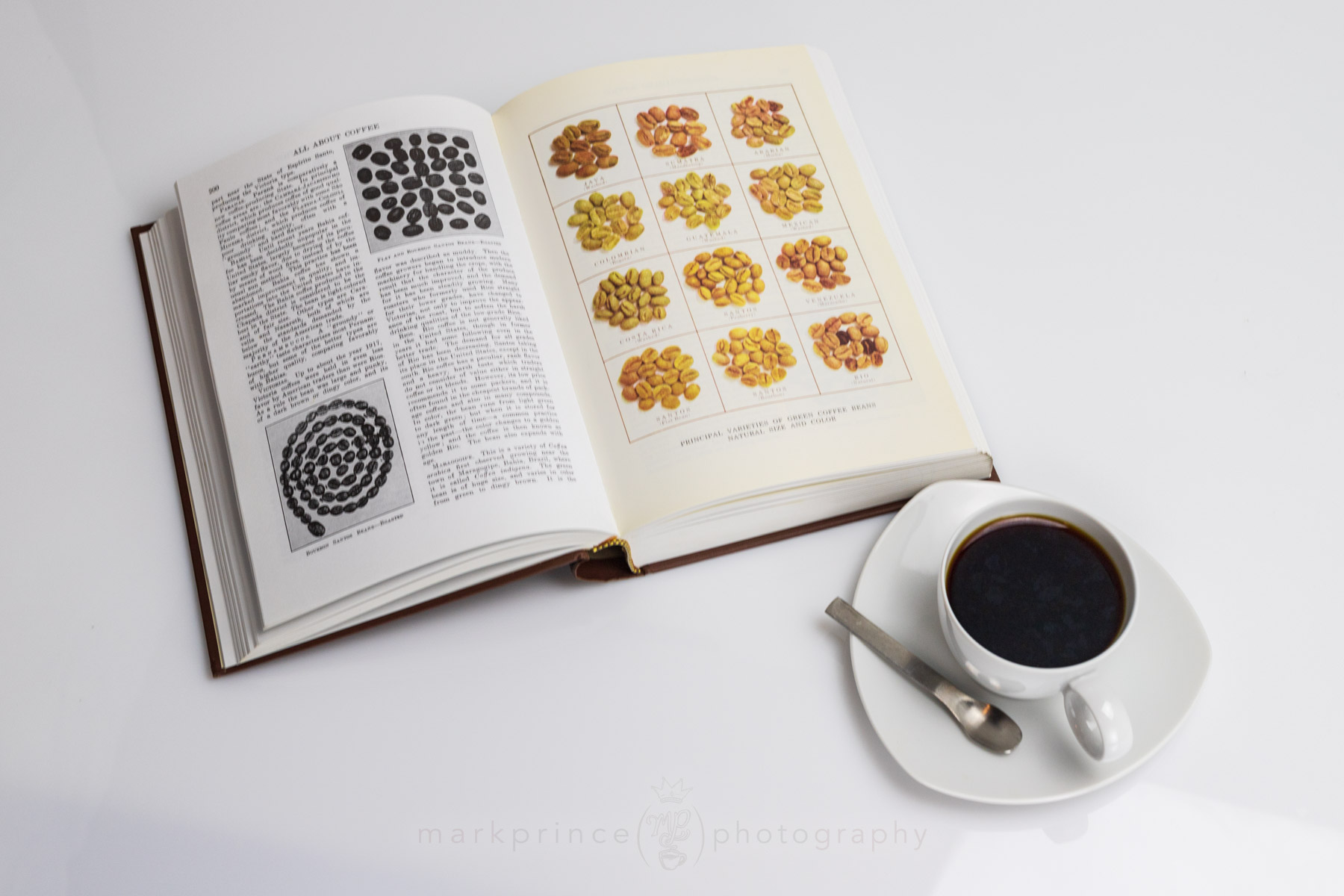

Ukers was the editor, publisher, and owner of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal (Note: the “The” as an official part of the magazine’s name was dropped in the 1930’s), which is still being published today by only its fourth owner in 122 years. He was also the author of many books, but it was his very first book, published in 1922, the encyclopedic All About Coffee, that became arguably the most important coffee book of the 20th century.

For decades, the only comprehensive book about coffee one could find, from its history to its science, was the all-too-correctly named All About Coffee by W.H. Ukers, as he is most commonly known. But let’s call him Mr. Ukers. According to a 2001 interview with James Quinn, who succeeded Ukers as editor and publisher of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, everybody called Mr. Ukers Mr. Ukers, even Mrs. Ukers.

About Mr. Ukers

Mr. Ukers was born in Germantown Pennsylvania in 1873 and was an honor student at the renowned Central High School in Philadelphia, from which he graduated at age 20 with a BA degree. Central High School remains today the only high school in the U.S. with the authority to grant a Bachelor of Arts degree if you do the work and get the grades. The school’s academic rigor has produced a long list of prestigious alumni including Nobel Prize winners, astronauts, Guggenheims, linguist and political activist Noam Chomsky, Penn of the magic act Penn and Teller, and Larry from the Three Stooges.

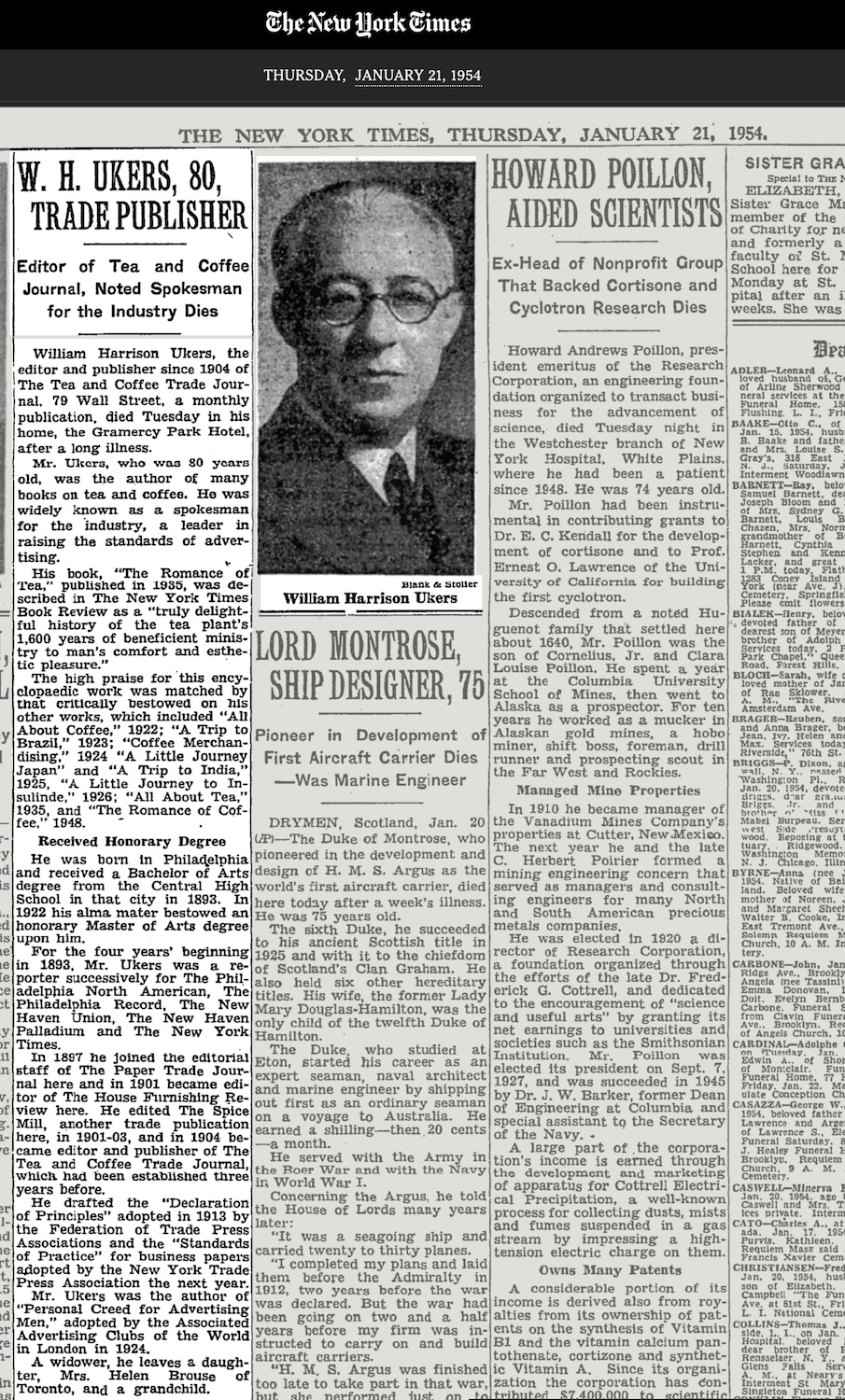

Ambitious and impatient following his graduation, Mr. Ukers pursued a frenetic career in journalism, writing for five different newspapers in less than four years, the last being the New York Times. New York would remain his home until his death in 1954. And please be assured, he did die in 1954 and not 1945 as tens of thousands of sources online, including the Library of Congress, would have you believe.

Not only did he write a letter to Albert Einstein in 1946 and publish his last book in 1951, but his obituary in the Thursday, January 21st, 1954, New York Times states that he died “Tuesday.” That date agrees with the final nail in the coffin as far as his death goes, his tombstone at Mount Hope Cemetery, 20 miles north of Manhattan, where January 19th, 1954, is literally carved in stone.

Following what appears to have been a short stint at the New York Times, Mr. Ukers moved from daily newspapers to trade magazines because, I must imagine, they offered more opportunity for moving up to the editor’s desk. He wrote for The Paper Trade Journal in 1897, then The American Stationer, and then a new publication just called “Paper” in 1899, where he also served as assistant editor. Soon after that he was made editor at House Furnishing Review. These dates can vary slightly among different sources.

Then what happened? Well, I’m not sure. I mean, I don’t really know why Mr. Ukers isn’t known today as the author of All About Paper or All About End-Tables. I don’t know how Mr. Ukers was introduced to the coffee and tea industries and how he came to decide they were being underserved by “industrial journalism” and so decided to start a tea and coffee magazine.

Whatever attention deficits Mr. Ukers appeared to display in his 20’s, they diminished significantly as he approached his 30th year and discovered coffee and tea. While these were not his only interests from this point forward, tea and coffee far-and-away dominated most of his attention. Like many of us who work in coffee, I suppose he stumbled into coffee and once it had him in its grip it never let go. What we do know, because Mr. Ukers tells us in All About Coffee, is that in 1901 the first issue of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal “appeared in New York.”

The Birth of THE Coffee Trade Journal

Why so coy and cryptic Mr. Ukers? Countless sources, including the masthead of Tea and Coffee Trade Journal itself, tell us that Mr. Ukers started The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal in 1901. And yet, I cannot find any record extant of Mr. Ukers saying this himself in print.

Exactly when and how Mr. Ukers became involved with The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal and his relationship to the magazine before 1904 is a small puzzle based simply on what Mr. Ukers himself writes about it, which is no more than this one sentence: “In 1901, there appeared in New York the first issue of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, devoted to the interests of the tea and coffee trades.”

Why, in the name of all that is caffeinated, didn’t he simply write “In 1901, William H. Ukers published in New York the first issue of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, devoted to the interests of the tea and coffee trades”?

There is a story repeated several times online that claims Mr. Ukers went to work as editor for a publication called Spice Mill in 1901 or 1902. That part is true (it was 1902 according to Mr. Ukers). Spice Mill was an internal company magazine, known as a “house organ,” published by Jabez Burns & Sons for employees and customers.

At some point, the story usually goes, Mr. Ukers determined that the industry needed an independent trade journal, and he thought Spice Mill could be transformed into an independent publication rather than a promotional publication for Jabez Burns & Sons. He pitched the idea to his bosses, and they said no thank you.

Mr. Ukers then picked up his marbles and went home and started The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal. In some versions of the story, he did this the very same day the Burns brothers rejected his idea of turning Spice Mill into an independent publication. Mr. Ukers’ successor, James Quinn, told a version of this story in 2001.

The problem with these stories is Mr. Ukers’ own written testimony, which contradicts the idea that he left his job at Spice Mill to start The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal. The dates don’t jive. However, it may be that he left Spice Mill to devote all of his time to The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal. He writes:

“A. Lincoln Burns succeeded his father as editor of the Spice Mill. William H. Ukers was made editor in 1902, and he continued until 1904, when he left to assume editorial direction of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal.”

Is it just me, or are we again with the cryptic here? If Mr. Ukers “assumed editorial direction” in 1904, what was his relationship to The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal before 1904? It’s a puzzle with missing pieces, enough to drive a storyteller to distraction. I have several theories, more appropriately explored on the first episode of my podcast, All About Coffee a Page-by-Page Podcast, where I can digress to my heart’s content (coming soon to a podcast service near you).

Suffice to say that the first issue of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal was printed in 1901. What it looked like, how it was distributed and how often, we don’t know. Whatever his involvement with the journal for its first three years, Mr. Ukers turned his full attention to management of the magazine in 1904. The U.S. Post Office granted The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal second-class postal rates in 1905 and Mr. Ukers was on his way to becoming a spokesperson and advocate for the coffee industry as well as its primary historian, documentarian, defender, and the chief curator of its ever-evolving science.

Although tea and coffee became his primary areas of focus and expertise, it’s clear he thought of himself and his magazine as serving the wider grocery trade. In 1908, taglines on the cover of the magazine cast a rather wide net and repetitively declare it was “The Recognized Organ of the Tea, Coffee, Spice, and Fine Grocery Trade” And “The Tea and Coffee Dealer’s Magazine.” The crowded cover of the magazine also announced that it was “The Blue Book of the Trade.” Sometime in 1920 the magazine started using what is my favorite of all the tag lines used over the years: “The Grocery Magazine De Luxe.”

I think we can all agree, once you become “De Luxe,” you’ve truly arrived.

Mr. Ukers was active in the association, “Grocery and Allied Trade Press of America,” serving as president in 1912. Within the pages of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, Mr. Ukers’ intention that the magazine serve the “fine grocery trade” resulted in a magazine we wouldn’t recognize today. In the early decades of publication, articles specific to coffee and tea would not generally take up more than 50% of the content.

A significant number of articles were devoted to good business practices in general, using businesses that fall under the rather large grocery trade tent as examples. There were also articles in most issues on spices, cocoa, sugar, and even rice. This makes sense for that era when few if any importers dealt exclusively in coffee. Most U.S. importers were selling a wide variety of commodities that were not produced in large volume domestically.

A rough sampling of Table of Contents and ad content in the years following publication of All About Coffee, for which The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal served as publisher, suggests a significant narrowing of focus to news and articles mostly about coffee and tea, though spices, cocoa, and sugar were still covered. This trend would continue until tea and coffee were virtually the only focus of the magazine.

In the same way that Mr. Hoffmann had established himself as a barista champion and respected coffee thinker and blogger before he published The World Atlas of Coffee in 2014, Mr. Ukers was well known as a coffee writer and spokesperson both inside and outside the industry before he published All About Coffee in 1922.

According to the bibliography in the back pages of All About Coffee, Mr. Ukers published consumer articles about coffee as early as 1908. There may have been—likely were—other earlier articles but in the book’s bibliography, he calls out only a few: “A Talk on Coffee” published in a 1908 issue of Good Housekeeping. (ed.note – he also wrote about tea in the same journal a few months later). In 1911 he wrote “Better Teas and Coffees,” also for Good Housekeeping. In 1909 he wrote “The Great Coffee Corner” for The Saturday Evening Post. (Note, the “Great Coffee Corner” refers to Brazil, several bankers, and a few large roasters working together to corner the coffee market and control prices. It didn’t work.)

Mr. Ukers played a role in rallying the coffee roasting industry to form the association that would eventually become the National Coffee Association. In addition to the Grocery and Allied Trade Press of America, he was also president of the New York Trade Press Association in 1915 and authored an influential essay titled “The Standards of Practice of the Business Press.” Following the publication of All About Coffee, quips and quotes from its pages appeared regularly in newspapers all around the world, always citing Mr. Ukers as a leading expert on the subject of coffee.

This might be a good spot for an interesting if almost entirely, but not quite, irrelevant aside: Mr. Ukers notes in the bibliography for All About Coffee that one Paul Hoffman (one “n”), a German author, wrote an article about the first century of coffee for a magazine titled “Journal of Cultural History” in 1901.

I mention this not only because I’ve somewhat shamelessly used our own James Hoffmann as an analog for Mr. Ukers, but because it’s clear that Mr. Ukers could read all the French and German books listed in his bibliography. His intellectual capacity was no joke, even if he feared that people considered his honorary Master of Arts degree, bestowed by Central High School just in time for him to include an “M.A.” after his name on the title page of All About Coffee, was something people might laugh at.

In his 2001 interview, James Quinn states that Mr. Ukers was clearly defensive about the honorary degree and would go to some lengths to explain and justify its import. Nevertheless—and notwithstanding his intellectual weakness and simple laziness when it comes to his colonialist racism, often delivered in what we would call “hot takes” today—the guy had a big giant brain. And while we might argue over whether his honorary M.A. was earned, it seems certainly deserved.

James Quinn joined Tea and Coffee Trade Journal in 1951 as Managing Editor. Fifty years later he would say, “If Ukers had a sense of humor, it was long lost by the time I met him. He was a very formal man when I went to work for him.” I don’t doubt Quinn’s memory here (even though he misremembers the year of Mr. Ukers’ death as 1956 in the same interview) because 1951 was also the year that Mrs. Ukers died.

Following publication of All About Coffee, Mr. Ukers went on to write many more books on coffee, tea, and travel. He even wrote a novel. All of his books were dedicated to his wife, Helen De Graff Ukers, and there is every indication that following their marriage in 1912, she was a full partner in the management of their magazine business. When James Quinn met Mr. Ukers, he was meeting a man who had recently lost or was about to lose his partner of 40 years and he would only live another three years himself. Surely, he was grieving. No wonder he had lost his sense of humor.

However, if you read Mr. Ukers’ little 1939 book, A Trip to Brazil, you’ll find a lively and enthusiastically informal first-person travelogue and coffee commentary that could not have been written, it seems to me, by a stuffy person with no sense of humor. In announcing the wedding in June 1912 of Mr. and Mrs. Ukers, California Grocers Advocate magazine described Mr. Ukers as a “decidedly clever young man” and “intensely interesting” with a “strong personality that makes many friends for him.” Hmm. Sounds like a YouTuber to me.

A Trip to Brazil also reveals that Mr. Ukers was something of a polymath, from his interest in and knowledge of nautical navigation, to quoting poetry in his journal entries. All About Coffee devotes 75 pages to coffee in art and literature, revealing a deep appreciation for creativity, which explains why I began this introduction to Mr. Ukers with Mr. Hoffmann as a musician.

You don’t need to be involved with coffee very long, as a profession and/or a passion, to discover that coffee attracts interesting people, many of whom could be or are successful in other endeavors. But coffee tends to sustain their engagement. It’s tempting to imagine this level of engagement is something new, an outcome of the specialty coffee industry where things are, you know, special. Well, maybe it’s more pronounced in specialty coffee, but I suspect this level of fascination has always surrounded coffee, as exemplified by both our once and future kings of all coffee media, Mr. Ukers and Mr. Hoffmann.

Postscript

If you are not familiar with All About Coffee, I think it is worthy of a spot in your library if you have more than a passing interest in coffee. But fair warning, it belongs among your reference books. Reading it cover to cover is no small challenge. Some of the sections listing the various “coffee men” who worked in various cities over the decades can read like genealogies in the Old Testament.

The book has been in the public domain for decades so print-to-order copies are easy to find online as are free digital copies of both the 1922 edition and the second edition Mr. Ukers published in 1935. Most of the updates found in the 1935 edition concern advances in the science of coffee at the time. Although there is plenty of dated material, there is less irrelevancy than you might imagine. In fact, as you skim the pages, I can almost guarantee you’ll find yourself thinking some version of “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Finally, good and recent news for those who prefer to listen to their content: In December of 2022, the volunteer readers at LibriVox Audiobooks finished recording a 40-hour audio version of All About Coffee, also available on YouTube.