I managed to get a few days with a copy of Modernist Cuisine, the absolute tome of modern cooking and culinary pursuits involving science and art. The entire breadth of the books are extremely enticing (I’d buy the books in a heartbeat if I could afford them), but I also naturally gravitated towards the Coffee chapter to use as a basis for review and for gauging just how thorough the books are in all aspects of culinary cuisine. I have a theory you see: if coffee is given nary a second look (be it in restaurants, in mass media, in journalistic media, or in food books), it causes questions about how that particular venue or literature handles other aspects of what they cover.

With that thought in mind, I delved into the Coffee chapter in Modernist Cuisine with gusto and anticipation.

Structure of the Coffee Chapter

50 pages are dedicated to the subject of coffee in all its main forms in Modernist Cuisine. There are several pages full of vibrant photography, and even more pages with visual step by step instructions, trouble shooting and the like. Some pages are meaty with text, others are with visuals, and still others feature more of an artistic layout.

The pages breakdown this way:

- Introduction to Coffee, Coffee Basics. 8 pages that cover the basics of coffee, how to store, decaffeinated coffee processes, stages of roasting coffee, causes-coffee (Fair Trade, etc), and (ugh) Kopi Luwak, which gets its own call out box.

- Brewing Coffee, 8 pages that cover introductory brewing principles, cupping coffee, the ExtractMojo (natch, for a sciencey book), types of brewed coffee from drip to press to siphon to pourover to aeropress to cold extraction, and one page is about cooking with coffee, including a recipe for coffee butter.

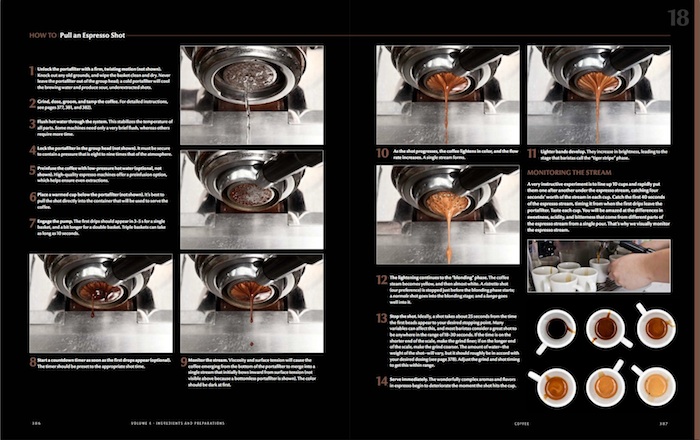

- Espresso which (thankfully) gets 32 pages of love and dedication. Covers some history, espresso in Italy, a nice side story about the “God Shot”, 3 pages about grinders and grinding, the evolution of shots (and spouts), how to dose, how to tamp, why water is important, info about chopped portafilters, brewing temperatures, a step by step how to photo essay, information on crema and a troubleshooting guide. Then there’s 6 pages that are milk focused (covered below), and the section rounds up with information and visual guides on achieving consistency. Towards the end of the chapter, there is some talk about Seattle’s espresso scene, and the latest in espresso, including pressure profiling machines and the Synesso.

- Milk. 6 pages within the espresso section. Covers basics of milk steaming with a visual how to, the art of coffee with milk, discussion on types of foam, a guide to drink types, and a 2 page layout on pouring latte art.

- Last Page is a photo of Synesso’s half-exposed 3 group Cyncra espresso machine with detailed explanations of what goes into the works.

That’s pretty comprehensive. So how deep and how real did Modernist Cuisine get with their Coffee Chapter? Did they cover just a few aspects of the coolest (or most trendy) things in coffee and espresso today, or did they take more of a long view on it all?

Modernist Cuisine Coffee Chapter – Introductory Section

Right away, I was intrigued by the opening paragraphs because this is how the chapter starts:

“Dining at a fine restaurant is such a special experience because so much attention is given to the smallest details of the meal: carefully chosen ingredients, artful dishes, sublime wines, classy cocktails, artisanal breads, refined cheeses.

Then comes the coffee, so often an after-thought — more like a generic commodity than a gastronomic event—that many people don’t even realize what a transcendent experience the beverage can provide.

This is true even at Michelin three-star restaurants. These pinnacles of the culinary arts boast the finest food in the world, proffer encyclopedic wine lists, and go to every extreme to offer the best dining that money can buy. Yet a typical Michelin three-star restaurant serves coffee that wouldn’t meet the standards of an ordinary street vendor in Seattle.”

Damn. This is starting off good. This argument has been made by so many people striving to make coffee better to a broader audience for so, so long. For it it to lead off the opening of the coffee chapter in one of the most hyped and anticipated cook books of all time… this is a good start.

The section continues giving a waxed poetic introduction to the joys of culinary coffee. It touches on the “young turks” of coffee today who are picking up the mantel from the pioneers and trailblazers. The section then smoothly moves onto describing in short form the cherry to bean road, types of processing, and covers the basics of roasting. The information is rich, and just brief enough that it shouldn’t bore most foodies, chefs, sommeliers etc. that may pick up a copy. But, though it is brief, everything is bang on correct in terms of quality coffee doctrine, and even the most seasoned coffee pro will either learn a thing or two from the first section, or at least refresh their memory about some definitive coffee facts.

A bit of a downer in this section of the Coffee chapter is the dedication to a half page on Kopi Luwak. I know, I know, everyone deep inside the specialty coffee industry is sick to death of it, but everyone else in food, (but not into coffee so much) probably wants to know more.

One thing I kind of call question to however on the Kopi Luwak callout: the book talks about how the acids in the civet cat’s stomach break down some proteins in the green coffee, and they leach out during the digestion process. These proteins normally contribute to excessive bitters in roasted coffee (so the book claims) so their removal through the digestion process results in more natural sweetness from the resulting roasted coffee.

I kind of call BS on that. I think that’s a Kopi Luwak marketer feeding information. If I can explain a bit further.

First, the bean comes out of the civet cat in all sorts of stages within the cat’s scat: some still have partial bits of undigested cherry; many more still have the mucilage (inner skin) attached, which is a protective barrier for the bean during its relatively short time inside the civet cat. I’m fairly confident that most, if not all the acid action happens to the outer coatings of the coffee bean (mucilage, pulp, skin) and very little to the inner depths of the dense green bean.

Secondly, though the book emphasises how much proteins contribute to bitterness in coffee, there’s scant mention of caffeine, which is literally one of the most bitter substances in found in nature. That said, yes there are proteins, lipids and other elements within a roasted coffee bean that contribute to bitterness. Hell, the roast profile contributes to bitterness. To say the cat-shit method of “producing” green coffee results in a smoother cup is just marketing drivel.

This is a nit-pick, and not at all indicative of the entire chapter’s correctness, but I would have felt better if they said something like “Kopi Luwak is a fad / gimmick coffee, and not worth your time even discussing”.

On to better things, there’s so much to like in this first section of the Coffee chapter in Modernist Cuisine. Little things like how a sidebar is used to blast apart the myth that “espresso” is not a type of bean or a specific type of roast. Fair Trade is covered quite, ahem, fairly (to everyone save for Fair Trade marketers and TransFair) by outlining its origins and how it has moved into more of a marketing gimmick. Direct Trade is touched upon (a good thing), perhaps leaving the reader hungry for a bit more (not so good).

Storing coffee is covered, and ends with the words: “…coffee should be ground immediately before brewing. We prefer not to store ground coffee.” Love it.

Another thing I really enjoyed about this section was how the author(s) went about pounding home some truths while obliterating certain myths about coffee. Case in point: “strong coffee”. They tackle this with sage, wise words in the brewing section, and find a way to clearly blow apart the myth that strong coffee requires dark roasted coffee. They also tackle the confusion consumers have with bitter vs. strong. You’ll have to buy the book to see how they wordsmithed this up, but trust me, it’s good.

I only wish they had taken on “bold” as well.

This section, along with all the sections in the Coffee Chapter, is filled with quite awesome photography. There is an excellent “Stages of Roasting Coffee” visual that covers from green to a full french roast and it is one of the most accurate colour photo representations I have ever seen on this particular subject.

Modernist Cuisine Coffee Chapter – Brewing Coffee

This section of the Coffee chapter really starts to get into the meat of what good coffee is about, and it does so with bam! a cupping how to (and explanation) and double bam! a two page spread on the ExtractMojo and a how to on using a brewing control chart. They ain’t dicking around here. This is some serious science of coffee to digest.

The George Howell school of sciencey coffee is in full effect here. From the brewing chart page:

“…experts agree that for a balanced taste, the extraction should pull 18% — 22% of total soluble materials (by weight) from the grounds into the water. If this extraction percentage (also called solubles yield) is less than 18%, the coffee tastes sour and astringent, if over 22% the coffee tastes bitter.”

This is absolutely current, state of the art thinking. Getting this kind of information into the heads of forward thinking chefs, culinary experts, and foodies is awesome. And I may have to pause here. This review (and reading the Chapter) is making me want to have a well-crafted coffee, something fierce. Perhaps thats as much a testament as anything as to how good this book’s coverage of coffee is.

Okay, back now, and leafing through the rest of the coffee section shows a lot of well grounded, well supported information on what goes into the act (art) of brewing coffee. All the major brewing methods are discussed, from drip to pour over (treated separately – yay!) from press pot to siphon brewing. Very thankfully, percolator brewing is ignored, save for perhaps a sideways nod to it when “cowboy coffee” is casually mentioned.

Siphon coffee is covered with some nice visuals. Given how siphon produces coffee and its rank amongst some of our best coffee professionals, I would have liked to see a bit more exploration of the method, but it is definitely covered adequately.

One thing that is perhaps missing from the actual coffee brewing section of the Coffee chapter is the grinder – or emphasis on it. Sure, it is mentioned here and there, and sure, later on in the espresso section, grinding gets star billing with lots of mentions, descriptions and photos, but it is perhaps too much de-emphasised in the non espresso part of this chapter.

That’s a shame because, well, I’m in the school of thought that the grinder is almost as important to press pot and manual pour over brewing as it is to espresso. It’s all about particle sizes and especially about the fines produced. I want to highlight – grinding is covered somewhat in the non espresso section, but also kind of brushed off as not being terribly important.

The coffee section of the Coffee chapter (how awkward is that statement?) finishes off with a bit about cooking — where I learned some new things — covering using fats or alcohol to extract from roasted coffee, and even a recipe.

Modernist Cuisine Coffee Chapter – Espresso

The fact that espresso and all that surrounds it gets almost 3/4 of the Modernist Cuisine Coffee chapter warms my heart. Espresso’s been getting a lot of beat downs lately as the current trend is towards (re)discovering pour over, press, drip, siphon, but you wouldn’t know that by reading these books. Makes sense too, since these books are beyond sciencey and espresso preparation is the most demanding, most exact, and most frustrating way to brew coffee.

I could easily type another 2,000 words talking about the espresso section in these books but instead, I just want to focus on a few things.

First of all, the scope seems to be just right for the books’ target audience. It gets incredibly in-depth on a lot of issues and circumstances surrounding espresso preparation, from particle distribution techniques (good!) to what temperature you should stop foaming milk and start just heating it (better!). Grind is super highlighted, as it should be. Tamping is given its due as well. Latte art gets lots of glossy coverage, which makes sense for the visual appeal (this is also a visual set of books, as well as being all sciencey). There’s even a breakdown (possibly slightly controversial) of what types of shots use how much coffee and produce how much brewed beverage.

The espresso section is definitely Seattle-heavy. A lot of the measurements, philosophies and produced items have a Seattle slant. David Schomer is mentioned multiple times and even gets a call out section. Very due, since Schomer is in many aspects the godfather of the North American espresso scene and often doesn’t get enough recognition from the current core of “young turks”.

That said, there are plenty of nods to the global espresso scene. There’s some nice info on how espresso exists in Italy, and some minor historical context. Several dosing techniques are described, including ones originating in other parts of the world.

The espresso section covers a lot about how great espresso occurs, and the tools to achieve it. Water is covered in a small but info-packed callout. Temperature control is heavily emphasised and given its rightful due in terms of making great extractions. They detail the nifty trick of segmenting shots of espresso to taste the beverage in parts. Crema is covered well, and detailed explanations as to why it exists are covered.

The chopped portafilter (they call it crotchless, and I really, really wish they hadn’t) gets lots of coverage as well, though perhaps it would have been nice to give a nod to the originators of it (Chris Davidson and others at Zoka back in 2004). That said, besides Schomer, few folks are actually recognized by name in the Chapter (one exception out of several is John Weiss, when his prolonged dosing and leveling technique is described).

New technologies are discussed, including some coverage of pressure profiling and the new machines on the scene capable of doing it. Preinfusion, pump pressures, troubleshooting (with pictures) – it’s all there, and as mentioned before – a heap of information, but just about right for the target audience for these books. There’s no mention of temperature profiling, but I guess since that’s the future of espresso and not the present, makes sense.

If I can nitpick, it’s just on a few things. I don’t agree with how much emphasis some of the “grooming” techniques got – I think most of that could have been pulled, and more emphasis on the grinder in the non-espresso sections could have been added. There’s also a lot of emphasis on automatic or clicker tampers (though the best clicking tamper – the Espro model – isn’t shown or mentioned).

And then we come to a call out that seemed a bit strange to me. It is a three-photo series talking about perhaps (my emphasis, not theirs) using a medical tool — a dental vibrating platform — to level and settle a portafilter. This just seems wrong to me, based on advice and discussions and experiments and more that I’ve had over the years. In 2003, I asked Dr. Illy why couldn’t we use a martini shaker to level and compact a bed of coffee in a portafilter, and his simple answer to me was (paraphrasing), “oh no, that would redistribute the fines to the bottom and damage extraction ability”.

In archaeology techniques, hypersonic shaking of particles (say, for instance, sand) will create a platform within a vessel of particles going from finest to coarsest in even levels. The same would probably happen to ground coffee, and there’s some theory as to why that is bad.

When brewing, the top of the bed of the espresso “puck” of coffee is impacted with enormous pressure – 135psi or higher. But the bed itself eats up and dissipates that pressure. By the time the liquid is at the bottom of the puck (about 1cm lower from its starting point), it is pretty much at normal pressure, relying only on gravity (with perhaps some minor boosts) to continue falling.

When you agitate the coffee-filled portafilter on a high-vibration device, it’s possible that all the finest fines will rapidly fall to the bottom of the basket. Water has more difficulty passing these fines. In addition, its possible you’re losing some additional extraction ability because instead of having these finest fines distributed throughout the bed of coffee (and thus causing more friction and interaction as pressurized water is slamming the grinds), these fines are all sitting near the bottom and just compacting into a more solid wall.

I could go on, but it just seemed this was not the greatest suggestion for settling a dosed bed of coffee in a portafilter.

Okay. So there were a few more contentious things in the espresso section, but frankly, they are all subject to bias and subjective interpretation. Instead, let’s end coverage of this section with some of the better things.

Cleaning a machine is hyper-emphasised and detailed. This is radically important, especially in books that chefs, restaurant owners, sommeliers, lead bartenders and more will buy. If there’s one thing that restaurants drop the ball on even more than coffee, it’s keeping espresso machines in their restaurants and bars clean.

And my favourite thing out of the entire espresso section? The God shot (a term born out of the alt.coffee crew in the late 1990s) is given a waxy poetic call out article which was simply awesome.

Concluding Thoughts on the Book

This is a mind blowing book in so many aspects. In the course of this review I could not help but read a good chunk of the books for hours and hours and hours; yet still, I only barely skimmed the surface.

Michael Ruhlman reviewed Modernist Cuisine for the New York Times, and at one point he stated:

“I was left wondering how a book could be mind-crushingly boring, eye-bulgingly riveting, edifying, infuriating, frustrating, fascinating, all in the same moment. Every time I tore myself away from these stunning pages to emerge for air, I had to shake my head so hard my cheeks made Looney Tunes noises.”

When I was reading (skimming, diving into, submersed in) other parts of the books, I felt that way and then some.

When I was reading the Coffee Chapter, not as much; but perhaps that is because coffee and espresso is a subject near and dear to me. However, I did get a good sense that a) the coverage was deep, and b) the stuff covered was honest. By and large, the chapter held a good balance between current trends and the long view on coffee and espresso development. The important things were almost always heavily emphasised, but since this is a geek out book, a lot of things that didn’t require as much attention got almost as much play.

The photos are stunning. Absolutely stunning. Unlike other sections of the books, Coffee never got the use an abrasive water-jet cutter or electrical discharge machining system to chop up the appliances or tools used in coffee or espresso. Perhaps that’s because our industry has already done those things with chopped portafilters and the half-exposed Synesso machine. Still, it would have been cool if Modernist Cuisine decided to do their own take on Illy’s transparent portafilter, but maybe they will for the 2nd edition.

All in all, coffee is very well handled in this tome. Coffee is respected, revered and romanticised throughout parts of this chapter. It has the scientific method bashed the crap out of it in spades. It is geeky. It is sciencey. It is romantic. It is beautiful.

Based on how Modernist Cuisine covers coffee, I feel quite confident that all other aspects of the culinary world are covered just as well, if not more so in this tome. Is this series of books worth $500, $600? Of course that depends on who you are and what value you put on this kind of organized, centralised information. But given the scope and range and depth involved, I’d say $600 is a bargain for Modernist Cuisine.

If you wish to buy Modernist Cuisine, the best prices are probably at Amazon.com (CG affiliate link).